#ManagementHeroes with John Gleeson – Head of Customer Success at KeepTruckin

Drive Your Team To Success: How a Head of Customer Success at Keep Truckin gathers information to make strategic decisions.

In a slightly modified version of Jack and the Giant Beanstalk, Jack clings to the beanstalk as it rapidly grows 🌱. While he physically doesn’t move, the rapid growth of the beanstalk changes Jack’s entire environment. He’s now required to do something, reinventing his process and confronting a giant. It’s a big change from when he started.

In a weird way, this is sort of what happened to John Gleeson. When he started as the Head of Customer Success for Upmarket at KeepTruckin 2.5 years ago, his team was small, around 5 people. But as KeepTruckin grew exponentially, John sort of shot up with it. While his role didn’t change in name, he went from managing a few direct reports to managing managers. Now his whole Upmarket CS team consists of about 40 people spread around the world (from Pakistan, to Nashville, to San Francisco). John needed to adapt to fit this new environment.

- How can leaders get better at making strategic decisions?

- So what does John do with all this information?

“It’s been just incredible growth. And so while my title hasn’t necessarily changed, and I think that the mission hasn’t really changed. When it comes to what I do on a day to day that’s evolved quite a bit.”

When his role expanded to becoming the manager of managers, John noticed three shifts. His new role had three key goals:

- To enable high-performing leaders who are already managers to do more with their team members.

- To strategically think about how he could best position people so that the different teams can be most successful in the wider scheme of the organization.

- To provide the team on the front lines with everything they need to be successful.

Instead of being overwhelmed by the challenges of reaching these goals, John approaches the process with enthusiasm and an analytical mind. At the core of overcoming these challenges, John finds it is easiest to make informed strategic decisions when you have a better data set.

“I think that the number one thing that I would say to a new manager is really focus on understanding or creating a better dataset for yourself by asking better questions,” says John.

How can leaders get better at making strategic decisions?

The first part is gathering information. To do this, John challenges himself to ask better questions. John’s dataset is a combination of quantitative and qualitative information. The raw numbers help identify lagging and leading indicators, renewal rate, and overall, are business focused. But this doesn’t always tell the whole story.

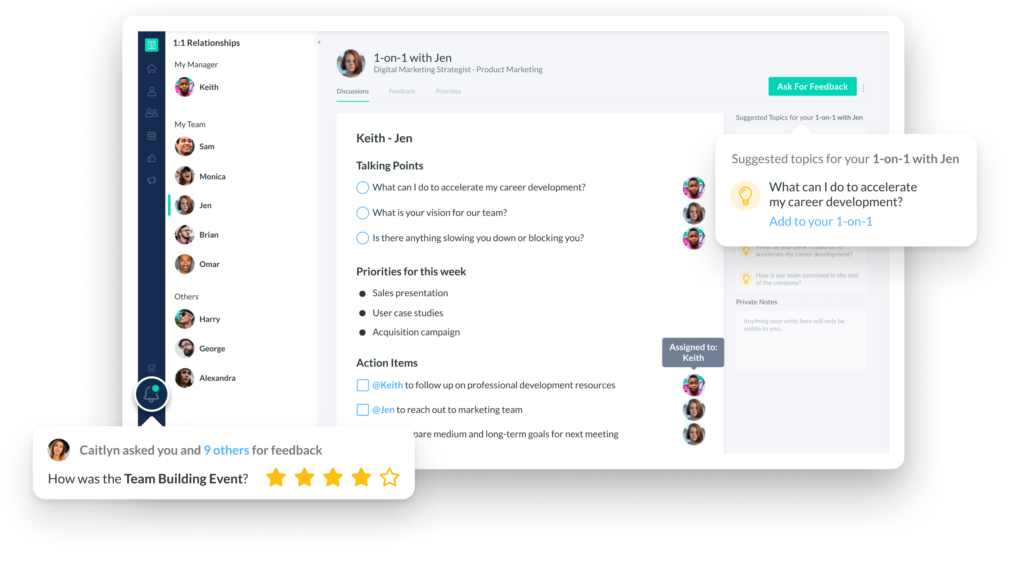

John gathers qualitative information for a variety of sources – 1on1s, skip-level meetings, surveys, and team discussions. Why the wide variety? It’s important to meet people where they are at. Some people are most comfortable giving written feedback, while others thrive in groups. If John were to depend solely on one source, he’d end up with a bias towards people most comfortable in that outlet.

“You want to meet your people where they are. Some people will be most comfortable sharing in a group-setting. Some people will be most comfortable sharing in a 1-on-1. And some people will be most comfortable sharing in written form. So I like to get information from a couple different angles.”

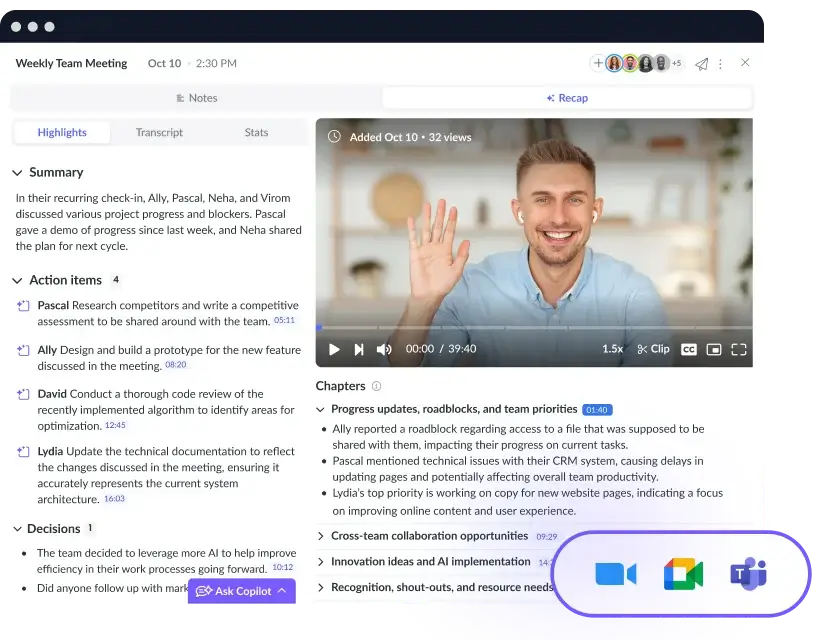

1 One-on-One Meetings

John’s weekly one-on-one meetings with direct reports are very much a “choose your own adventure” for the direct report. Prior to the meeting, John’s direct reports write a list in Fellow of all the things that they want to talk about or what is top of mind. John adds what he wants to talk about at the bottom and leaves in any duplicates.

For the first 10 minutes, they just chat about life in general to get to know one another as people. It’s especially important if you’re not in the same office. Imagine all the things you might talk about with someone when grabbing your morning coffee and incorporate that in your one-on-one. As John says, “It’s just being friends.”.

“I use those meetings to create trust, and then take the pulse so that I can have a better dataset. So hopefully, I can make more right decisions for my people.”

John has noticed that using Fellow has helped ICs (individual contributors) be more prepared for their one-on-ones with their managers, which helps facilitate more productive one-on-ones conversations.

Fellow helps leaders have great 1-on-1s and team meetings

2 Skip-Level Meetings

John finds it extremely important to hear directly from people who are on the front lines, interacting directly with the customers. In his own words:

“People on the front lines are seeing how everything that we are doing at the leadership level is impacting our customers.”

John aims to have quarterly skip-level meetings, and opens up his calendar in case anyone wants to talk. He keeps these skip-level meetings frequent enough to help build trust so that the employee knows that it is a safe spot.

These meetings appear inherently terrifying on paper, so John tries to create a comfortable space for his team. These meetings are often done while walking and John avoids taking written notes so that whoever he is talking to doesn’t feel the pressure of being on record. He asks them:

“Where are my blind spots?” or “What am I not seeing?”

The goal is to gather information at different levels of the organization.

3 Team Surveys

John occasionally sends surveys to the group to rate an idea or ask open-ended feedback questions, – something that can be done with the Feedback section in Fellow.app to keep everything in one place.

4 Team Meetings

Each week, John holds two team meetings: one with the entire upmarket Customer Success team and one with just his managers.

The large meeting aims to encourage everyone to go into the week feeling really good and updated on any important developments.

In the weekly meeting with just his managers, John tries to keep it as informal as possible – “It’s a Friday afternoon”. These meetings are a sort of temperature check for John to learn how his team is doing going into the weekend. It’s a sort of rest period, a place to vent, and bounce ideas. Group discussions can be valuable to develop and build on an idea.

Additionally, as a leader in Customer Success, John has a lot of cross-functional team meetings. He’s found it helpful to be the designated meeting note-taker and assigning clear action items using Fellow. With so many meetings, it also helps to have all the notes and action items all in one place. John admits he’s not a naturally organized person, so Fellow helps him stay organized in a single place with a source of truth.

So what does John do with all this information?

The end result of asking better questions is uncovering better information. It comes back to the three key goals!

1 Enable high-performing individuals who are already managers to do more with their team members

In his experience, John found that the transition between IC and manager was similar to the transition between a manager and a manager of managers. For an IC shifting into a manager role, John recommends asking better questions.

“Your job becomes trying to get them to look at the problem in a different way and enable them to solve problems for themselves,” he says.

As in a lot of organizations, the best IC gets promoted to manager. It’s easy to fall into the pattern of jumping in and micromanaging the task.

With the shift from manager to a manager of managers comes different challenges that need solving. Your direct reports have different problems that they need advice for. The goal is to coach your managers on how to solve these problems in the future, providing time for you to scope out other things.

John asks questions to help someone consider a different strategy/lens, and encourages them to figure out how to solve their own problem, to know how to solve the problem in the future. As the saying goes, “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for day. Teach a man to fish and feed him for a while.”

“Now you’re working with your managers to say ‘ok, when this comes up, here’s a framework you can use to solve it’. And just ask better questions of them so that they can solve their own problems,” says John. “And that will give you the time and space so that you can start to look outwards in the organization and understand strategy or things that you can get ahead of and that really becomes your job – to be proactive not reactive.”

2 Strategically think about how he could best position people

Having the information necessary allows John to see all the factors on the playing field – and make proactive strategic decisions. He then plans his next move, figuring out how he can make his team as great as possible.

John identifies team strengths and thinks about where/what will give/get them the most value. As John explains, not every hockey player is Wayne Gretsky. But a team filled with clones of Wayne Gretsky would be much less productive than a balanced team – Wayne Gretsky never played goalie!

“They each have different roles to play. But together if you know what that team or that organism looks like you can be in the best position to move the whole thing forward.”

This team-first mentality is best exemplified in how John gives feedback. As a naturally positive person, John reflects that he tends to be less critical and have too much empathy about the parts that are not perfect. To try and get around this, John first acknowledges what his natural baseline is and decides to frame things in a way to make them even more positive. For example, this person is great and if they did this then they could be even greater!

He also frames feedback in a utilitarian way – that the collective whole is most important and is only as strong as its weakest performer. Now he makes sure to not let any one thing slide – while this might be painful for one person, he reminds himself that this might also be causing pain to far more people.

3 Provide the team on the front lines with everything they need to be successful

John values helping his team be the best that they can be. It’s a “Multiplier” type of leadership where a leader supports his team to give more than 100% as opposed to a “diminisher” who takes control and dominates their team.

The authors of the book Multipliers, Liz Wiseman, and Greg McKeown describe these multiplier leaders as:

“At the other extreme are leaders who, as capable as they are, care less about flaunting their own IQs and more about fostering a culture of intelligence in their organizations.”

Part of the culture of KeepTruckin is to discuss an individual’s superpowers. It’s about finding tasks that make the team excited and energized.

“Multipliers see themselves as coaches and teachers. They enable others to operate independently by letting people own their results and rewarding employees’ successes. These leaders put a high premium on self-sufficiency: Once they delegate a task or decision, they don’t try to take it back,” say Wizeman and McKeown.

Overall, John has found the key to driving his team forward is to learn as much as you can about the people, the challenges, and the dynamics.

Once you get all the information, it’s easier to think of a big picture and put all the pieces together.

With all that information, you can be “Proactive, not Reactive,” as John frames it 💪.