Camille Fournier: Why Leadership Requires Self-Awareness and Maturity

How to diagnose a culture of fear, create a career ladder within your organization, and receive constructive feedback from your team.

Camille Fournier is the Managing Director of Platform Engineering at Two Sigma and the author of The Manager’s Path: A Guide for Tech Leaders Navigating Growth and Change.

In episode 24 of the Supermanagers Podcast, Camille talks about the art of managing technical teams and why leaders should always strive to develop and improve their own skills.

Listen to this episode (or read the transcript below) to learn about the importance of self-awareness, repetition, and structure in leadership.

1 In the beginning of The Manager’s Path, you wrote: “The secret of managing is keeping the people who hate you away from the ones who haven’t made up their minds”. What were you thinking when you put that quote there?

I am not a person who takes herself super seriously, for better for worse. And I, you know, a lot of The Manager’s Path was about the mistakes I made along the way of becoming a good manager (whether I am a good manager now or not. You’d have to ask my team).

I do think that for a lot of new managers, you’re gonna screw up. And you’ve got to be kind to yourself through these screw ups, you want to learn, you want to grow and move on from failure. Don’t get too hung up about trying to be perfect.

As you start this process, there’s always new things to learn. And don’t take yourself too seriously. I guess that’s that’s the inspiration for that.

2 Who has been your most memorable or favorite boss (and why)?

I think my favorite boss is a guy named Mike Marcel. He was my boss for several years at Goldman Sachs. The thing about him is that he has managed people, he may manage people now I’m not actually sure, but he’s definitely not a traditional manager like I have become, you know, I have definitely myself followed the manager’s path as it were right. I manage big teams, that is my career.

He managed me the first time that I managed people, I became the tech lead and manager for a subset of this very small core team that I was on at Goldman. And he was the first person, he was the first person to put me in a management job, that was still actually very technical, which was what I wanted to do.

So he’s my most memorable manager, probably because he was, first of all, just like a wonderful human being and very smart. He taught me how to really lead big challenging projects, and how to deal with people who are sometimes a little bit challenging themselves. And I think that he just set me up to be a thoughtful manager… but also to realize that you can be a manager, or you could be an IC (Individual Contributor).

He made it clear that you don’t have to manage big teams if you don’t want to. But if you’re gonna do the management thing, you owe it to the people you’re managing, even at a small scale, to do the best job.

I really respect him for that. I just learned so much from him. I remember him most for being so good at pushing me and the team. Without being cruel or hard on us.

I remember him for things like telling me: sometimes you gotta stop thinking and just start, start coding, start writing, start whatever, right? Sometimes the best thing to do if you’ve been in your head for too long on this topic, just start doing something you’re going to learn more, if you just start.

He was the person who really taught me how to really run a long running hard infrastructure project and how to plan a project like that, at the level of detail that you need to be able to plan it to be able to be reasonably sure that you’re going to be successful. And that was a very painful process of me bringing a plan to him. And him saying “not good enough, these areas… you need to go back and get a lot more detail on”. And me doing that over and over and over. I just remember it as being several passes through that before finally getting to something good. And that was one of the most, it was a very hard process. But it was so important. I think, for me, learning a set of skills that I just don’t think I would have gotten to where I am today if I hadn’t learned them.

3 Why is repetition a core element of leadership?

Everyone’s busy, right? And everyone has their own ways of thinking about things. We often don’t take the time to make sure we really understand what someone was saying to us, like I do it too. I think I’m a pretty good communicator. But there are definitely times when people say things to me, and I am sure that I know exactly what they want, and exactly what they’re saying. It turns out when we regroup on the topic, I thought X and they thought Y and those two things were very, very far apart.

I think that part of it is that, you know, when you have to repeat yourself, sometimes it’s a matter of look, you actually aren’t that clear of a communicator, and also you’re being run through someone’s mental filters, or whatever those mental filters are. So, saying it three times, saying it in three different formats, helps them triangulate right to what you mean.

If your boss hears it a bunch of times, they’re finally gonna realize: oh, this person is serious about this thing. They brought it up repeatedly. And that means I really need to do something with this.

Everyone is busy, and sometimes repetition is what’s needed to help people know that you’re really serious. Because if if you all you do is jump at every single hint of an idea, or an instruction or an issue or whatever, you will find yourself overreacting way too much.

I think everybody knows this, hopefully, my engineering team knows this to some extent, right? But there are times when you know, as a manager, you’ll realize: Oh, crap, I didn’t realize that they took that thing I said as an offhand comment, as like an instruction to go change several roles. And I think experienced people who have been through that, realize that if the boss is really serious, she’ll say it again. Or, you know, they know how to check the seriousness of a statement.

We’re all human. We’re all busy. We’ve all got our own impressions of things, repeating yourself helps it sink in also to really understand what you’re saying and makes it clear that it’s serious.

4 In the book, you talk about organizations with a flat structure. Is there a place for them, or is structure necessary from the get go?

If you’ve got three people, and you’re obsessing over titles, it’s not particularly healthy. And I think that when you’re in a very small group, where the mission is so incredibly clear about what you need to be working on, there’s more than enough work to go around for everyone. And you all feel reasonably equally incentivized. You’re all really bought in on the mission.

I think that in those situations it’s okay to have very little structure or very lightweight structure. I am sort of forgiving in those very small, very, very early teams of not worrying too much about structure.

I do think that once you start to grow and mature a little bit, once you quickly find that human politics and human habits start to come into play. If you don’t have any structure, and you’re starting to get tons of people, then the structure becomes whoever the earliest employees or whoever is best friends with the CEO, or whoever is loudest in meeting.

Having structure be this kind of informal thing leads to uncomfortable situations where, you know, people feel bullied, they feel like their ideas aren’t being heard.

There’s always some kind of hidden hierarchy, right, sort of shadow hierarchy that’s happening, where, you know, people who have the informal power or wielding it to decide what happens and what doesn’t. And I think that tends to breed unfair behavior. It doesn’t even have to be bias behavior or unethical behavior. It can just be like: “it sucks that the boss’s buddies are the only people who get to make decisions.” People are going to resent that and that undermines the cohesion of the team.

5 When should leaders start to formalize team titles and implement a company structure?

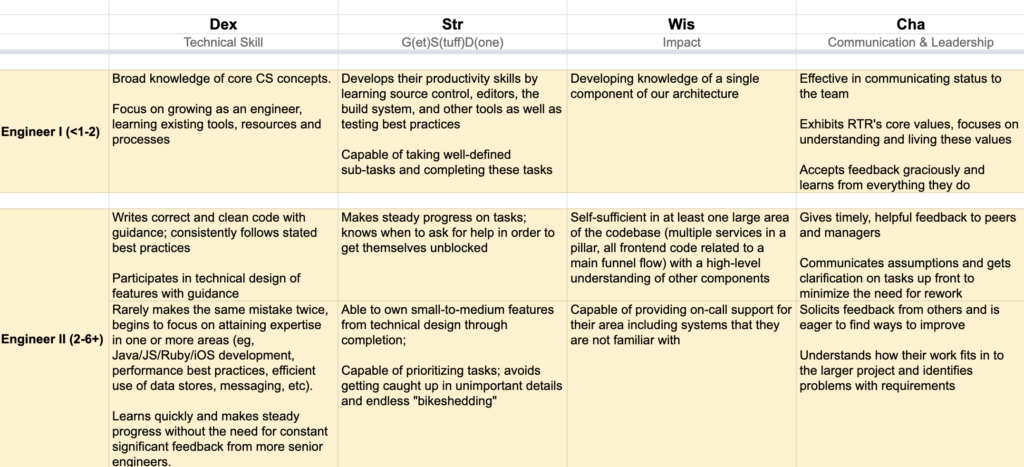

I think one of the things that I probably contributed to in the tech industry and I think is mostly for the best (but I’m sure some people hate me for it) is the formalization of engineering ladders. There’s a whole bunch of them published on the internet now, and I was one of the early people to do that.

I think a lot of engineers expect that even at somewhat early stage startups.

- Where’s my career going?

- How do I become a senior engineer?

- How do I become a manager?

I think that it’s harder these days to have teams that have really no structure and no career path, even at somewhat early stages, right? It’s probably it’s really good to have some kind of teams, and you may need to have some distinction of like, “these really are the more senior people”, but I don’t know if it’s really that necessary.

Once you start to get to 20, 50, definitely. You want some kind of structure. It’s very hard to coordinate 50 people without any structure at all, especially if you don’t have managers.

You’re probably going to want to have senior folks to teach the less senior folks, that can oversee some some technical decisions, or product decisions, or whatever. So you’ve got structure that’s coming in, whether you officially have it or not.

So I definitely think that somewhere above 10, and certainly, well, below 50, you want to have some structure, and you can decide how much you want to put in, in the early days, it’s always easier, I think, to add a little bit more structure than it is to take it away.

I’m certainly in the case of engineering, career ladder type things. I’ve seen and heard about companies who had a lot of levels, and then they were like, oh, we’re gonna roll back to having fewer levels, that tends to not go very well. It’s almost always a little bit easier to add more. Adding is always tricky. It’s always a little bit fraught. But these are things you do need to really start thinking about, between 10 and 50.

Your team is going to want it. You’re going to want to be able to offer them a career, a feeling of career progression, you’re going to need to have managers and senior Technical people. You’re delegating decisions, and those people need to have some more open authority in their roles.

It can’t just be the sort of shadow authority of who yells loudest or who is the boss’s best friend. I think at that point, also, you can’t necessarily know everyone super, super closely to actually know who is the right person to make every single decision. So this is also scaling for whoever’s in the leadership role.

6 Learning happens when we study our successes as well as our failures. Can you tell us about the time you got feedback about creating a “culture of fear” and what you did about it?

That was certainly a very memorable moment in my career, getting that performance review. It says a lot about everyone involved in the situation, the people who are willing to write that feedback and share it with my boss, my boss probably wanted to share it with me.

I’d like to think that it says something about me that I took it, and I tried to actually do something with that feedback.

My early years of my career, mostly were spent at Goldman Sachs and the culture at Goldman at the time was definitely a little bit… top down. “The boss tells you what to do” kind of culture. There was a lot of yelling in general. It’s hard for me to think about it now.

I didn’t personally get yelled at, for whatever reason managed to escape it, but I was around it – and I certainly internalized it.

Now I’m at Rent the Runway, I’m running this engineering team. I’ve never done this before. I’ve never run a team at this scale, the systems are very unstable, because we’re a startup and we’re going through this big rewrite, you know, the people are unstable, because it’s a startup and, people quit startups all the time, even when you’re doing great work.

It was a super special situation, I was actually pregnant with my first child, there was a lot going on, and I had these very high standards, they weren’t being met, I was stressed out, I was in a high pressure situation.

The result was basically that, I was just not behaving well. I was getting really mad at people when things went wrong. I was blaming them, I was definitely yelling.

So I get this feedback – and I’m like… well, crap… that is not the person I want to be. I think of myself as nice and fun. And you know, I don’t take myself too seriously. But I’m also super intense and super opinionated, and can be very intimidating.

I had to really take a step back and really start working so I had to work on:

- How am I communicating with people when things go wrong?

- Am I losing my temper? Or am I taking a breath?

- Am I picking when I think something is really important? And when I’m just in a bad mood, or, you know, not feeling good about it?

I’m still an intense person, I still occasionally get feedback about being intimidating. And I’ve just had to work really hard on controlling my own emotions, and finally becoming mature.

A lot of growing to the most senior levels and in leadership is about maturity. A lot of us, I think, have this mental image, that if you’re smart enough and talented enough, you can get away with being a jerk and still become really successful.

That’s obviously clearly sort of true, because there are plenty of successful jerks out there. Let’s not pretend like there’s not not some truth there. Most of us are not good enough to do that.

I did a lot of work. I had a coach and multiple coaches that I’ve worked with, when I was at Rent the Runway just on being aware of my reactions, being aware of the way I’m communicating, people meditating, you know, doing a lot of personal introspection work, thinking about how I relax and unwind.

I’m just aware of the person I’m being in various circumstances, learning to let go and trust my team a little bit more, setting up processes by which my team could show that they were doing things so that I would trust them more to some extent.

I think that helping the team perform better helps me be less scary, because I was less stressed out. And so it isn’t, there’s a little bit of like a virtual cycle that happens, right? You know, you apologize to people. I definitely spent time acknowledging:

“I’ve screwed this up, guys, I hear this feedback. Thank you for giving me this feedback. I am going to work on it.”

I’m actually doing a similar thing right now, I did a 360 review this year. And you know, some of the feedback was still that, like, I’m still on the critical side of things, right? I’m not creating a culture of fear. I don’t think most people who work for me would say that anymore, I hope. But, you know, there’s still shades of that in me.

So again, I’m going through the process of “I’m sorry that sometimes, I’m not my best self, I get too critical, I shut things down. I’m not bringing an open mindedness to my interactions, that creates a negative cycle.”

My goal with all of these things is work on myself and give the teams opportunities to do well. If I feel better, they feel better.

Things just get better in that way. But this was a multi year thing. I think by the time I left Rent the Runway, three years later, after that review, like nobody would say that I at that point had a culture of fear. But it probably took at least a year and a half to two years after getting that feedback before I felt like I had really done a pretty good job of getting away.

7 What advice or resources would you share with other managers and leaders looking to get better at their craft?

The best managers are working on it all the time. There’s always more to learn always more to grow. I think it’s really important to figure out, where do you need to develop, to be the person you sort of want to be, and that can be either, like from a career perspective, but also just from the way you interact with people perspective.

My guess is some of your listeners are just amazing people persons and maybe the thing that they actually need to really develop is having hard conversations with people, give them hard feedback, etc.

Don’t shy away from the things that are hard for you. If you really do want to be great at this job, it’s going to require getting out of your comfort zone, and learning.

The other thing I always have to remember is, you got to be open minded. Nobody knows everything. Every situation is a little bit different, right? People aren’t computers.

There’s no like one trick way to deal with every kind of person, I could not actually give you the formula for being the right manager because that formula changes all the time. There are things that I wrote about in the book that I did, and then I didn’t do and now I’m doing again, because they’ve worked in some situations, and they didn’t work others.

Stay open minded, keep learning, listen to your people. Even if you’re learning stuff that has nothing to do with management, you’re going to go into work every day, and you’re going to be more energetic and open and positive and fun.

I think the act of always learning is a very powerful one. That is my final advice.